South Asia, a region characterized by its majestic mountain ranges, vast plains, and life-giving monsoon rains, is increasingly at the forefront of the global climate crisis. While monsoons have always been a cornerstone of the region’s agricultural and social fabric, recent years have seen a terrifying transformation of this predictable weather pattern into a harbinger of devastation.

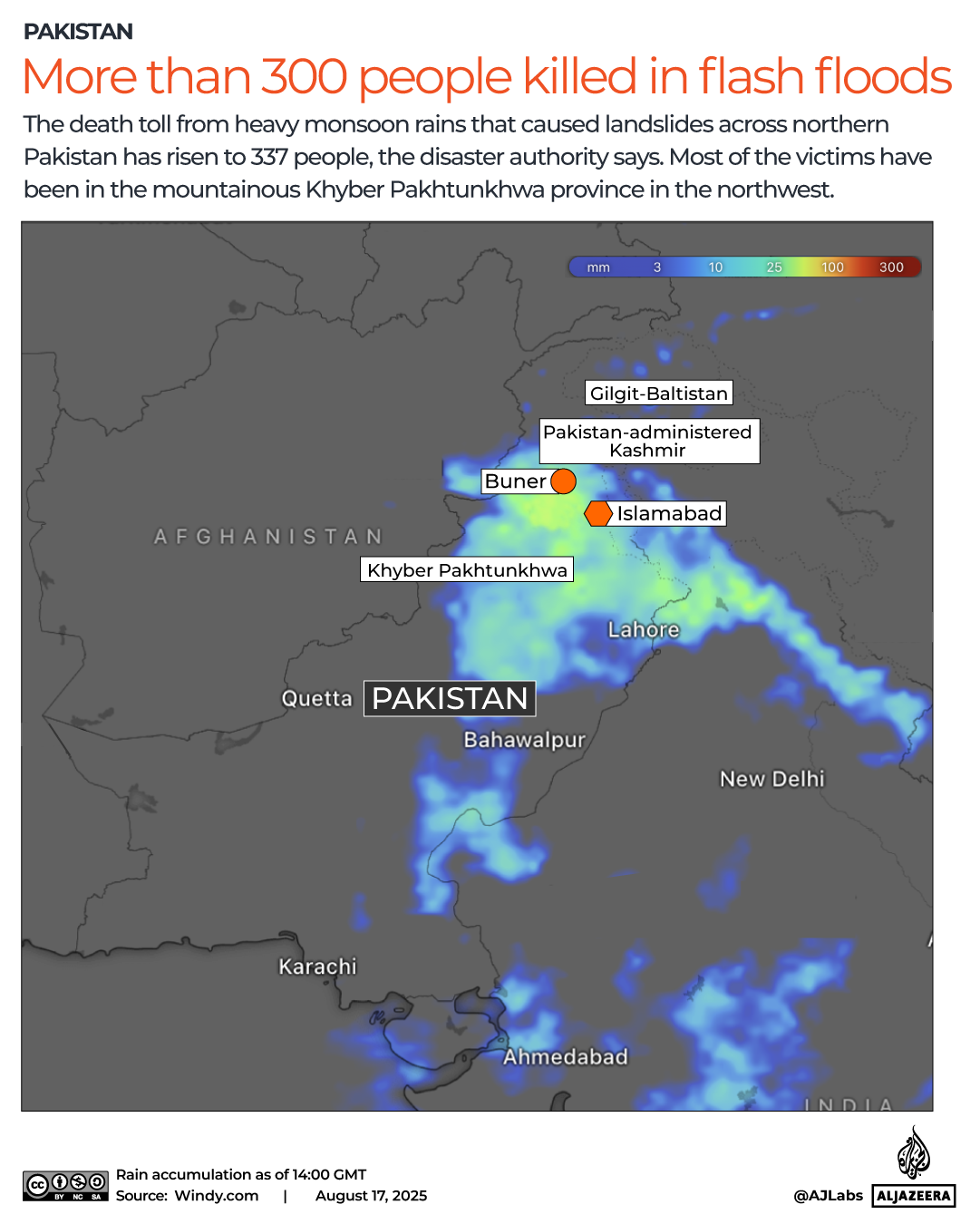

The recent flash floods in parts of Pakistan and India serve as a grim reminder of how climate change is amplifying extreme weather events, turning routine seasonal rains into lethal torrents. The scale and frequency of these disasters are not merely coincidences but a direct consequence of a warming world.

Source: Al Jazeera

A Supercharged Monsoon and Melting Glaciers

The direct impact of climate change on the recent flash floods is undeniable and twofold, a supercharged monsoon and accelerated glacial melt. A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture for every 1°C of warming; the air can hold about 7% more water. This fundamental principle of atmospheric physics is turning the monsoon into a volatile and concentrated force. Instead of widespread, sustained rainfall, the region is now experiencing “cloudbursts,” where an immense amount of rain falls in a very short period over a localized area.

These sudden deluges, often exceeding 100 millimeters of rain in an hour, overwhelm natural and man-made drainage systems instantly. Pakistan’s recent floods saw rainfall that was 10-15% heavier than it would have been without global warming, while the devastating 2022 floods saw a shocking 784% increase in rainfall in some provinces compared to the August average.

Concurrently, the Himalayas, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush mountain ranges often called the “third pole” due to their vast ice reserves are experiencing unprecedented melting. The heatwaves that preceded the recent floods in both countries exacerbated this process, destabilizing mountain slopes and creating an environment ripe for disaster. The melting glaciers and snow feed into rivers and streams, raising water levels and making them more susceptible to overflowing when combined with intense rainfall. This confluence of heavy rainfall and increased water from melting ice creates a perfect storm for flash floods, landslides, and mudflows, as seen in the mountainous regions of both Pakistan and India.

The Systemic Failures, and Human Vulnerability

While climate change is the primary driver, a critical analysis of the root causes reveals that human factors significantly amplify the scale of the damage. For decades, both Pakistan and India have grappled with poor urban planning and weak governance. Settlements are often built in high-risk zones, such as riverbanks, dry riverbeds, and drainage basins. These structures, frequently constructed from fragile materials, are no match for the force of flash floods. Weak enforcement of building codes and a lack of land-use regulations mean that development continues unchecked in vulnerable areas, putting communities directly in harm’s way. The casualties from the recent floods, where many deaths were caused by collapsing homes, are a stark testament to this systemic failure.

Pakistan and India are experiencing excessive #heat.

To avoid more and more people suffering from climate disasters, we must

👉 increase investments in adaptation

👉 halve emissions by 2030Dataviz by @ScottDuncanWX pic.twitter.com/Ax9XqRMaU5

— UN Climate Change (@UNFCCC) April 28, 2022

Furthermore, environmental degradation plays a crucial role. Widespread deforestation, particularly in hilly areas, strips the land of its natural ability to absorb water. Trees and their root systems act as natural sponges, slowing down water runoff and preventing soil erosion. Without this protective layer, rainwater cascades down hillsides at an accelerated rate, carrying with it mud, boulders, and debris, which magnify the destructive power of flash floods and trigger deadly landslides.

The development of hydroelectric power projects in fragile ecosystems also poses a threat, altering local water flows and increasing the risk to nearby communities. The combination of a warming climate and a lack of adaptive infrastructure and environmental management practices has created a vicious cycle of vulnerability, where extreme weather events, though fueled by global emissions, inflict their most severe consequences on the least prepared.

A crucial, yet often overlooked, aspect of the recent floods is the socio-economic disparity that magnifies the human toll. The poorest and most marginalized communities, who often live in poorly constructed homes on unstable land, are the first to be displaced and suffer the greatest losses. Their livelihoods, often tied to agriculture or daily wage labor, are obliterated, pushing them further into a cycle of poverty.

The lack of robust social safety nets and a fragmented disaster relief system means that they are left to fend for themselves long after the floodwaters recede. While the wealthy and well-connected can rebuild, the poor face a long and arduous road to recovery, often without adequate support. This stark inequality is a critical dimension of the climate crisis in South Asia, where the burden of global emissions is disproportionately borne by those with the least capacity to cope, making climate change not just an environmental issue, but a profound matter of social justice.

Conclusion

The destruction and loss of life in these recent events are not just a result of the weather itself, but a consequence of a deeper crisis of preparedness and governance. While the world’s focus is on global emissions, the immediate challenge for countries like Pakistan and India is to build resilience through proactive adaptation strategies, including robust early warning systems, climate-smart urban planning, and large-scale afforestation efforts. Without addressing these local vulnerabilities, the human cost of climate change will only continue to rise.