A High‑Stakes Legal Landscape

Investor‑State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms, commonly embedded in Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) and Investment Treaties with ISDS Provisions (TIPs), have played an outsized role in recent legal skirmishes between foreign investors and Pakistan. These cases have had concrete ramifications: multi‑billion‑dollar arbitration awards, revisions to Pakistan’s investment policy, and, critically, the erosion of investor confidence.

Landmark Cases

The Reko Diq Dispute

The most significant ISDS case against Pakistan is Tethyan Copper Company Pty Ltd versus Pakistan, filed under the Australia‑Pakistan BIT. This stemmed from the termination in 2011 of the Chagai Hills Exploration Joint Venture Agreement (CHEJVA), originally executed in the 1990s between the Government of Balochistan and BHP, later transferred to TCC. By 2006–2011, TCC had invested over US $220 million in exploration and project development.

Source: Tribune

After the provincial government revoked its mining lease in November 2011, TCC initiated ICSID arbitration seeking approximately US $11.43 billion in damages. In July 2019, the tribunal awarded US $5.84–5.976 billion, including interest and costs, concluding that Pakistan breached fair and equitable treatment (FET) obligations and unlawfully expropriated TCC’s investment. jusmundi.com. Enforcement efforts, including attachments of Pakistani state assets in the British Virgin Islands have posed serious fiscal and reputational risks. A March 2022 out‑of‑court agreement was later reached with Barrick Gold to revive the project under restructured ownership and investment terms (estimated at US $10 billion) while foregoing arbitration penalties. brecorder.com.

Source: Business Recorder

The Karadeniz (Karkey) Powership Case

In March 2013, Turkish energy firm Karadeniz Energy (Karkey) launched an ICSID claim against Pakistan over the annulment of a power‑purchase agreement and the seizure of Turkish powerships (MV KPS Kaya Bey and Alican Bey) in Karachi due to alleged payment and fuel delivery failures. After interim suspensions and eventual release of vessels in 2014, the tribunal in 2017 ordered Pakistan to pay a record compensation (exact amounts undisclosed). The dispute was later settled diplomatically by November 2019, under political intervention.

The Broadsheet / UK High Court Judgment

Broadsheet LLC, a US‑based firm, successfully enforced arbitration awards in UK courts in late 2020 and early 2021. Pakistan was ordered by the London High Court to pay US $28.7 million plus interest, charged against Pakistan’s High Commission in London. Pakistan ultimately accepted the judgment while pledging to challenge it, amid concerns over foreign asset attachments.

Source: Profit

Other ISDS proceedings have involved companies such as SGS (Switzerland), where Pakistan contested the tribunal’s jurisdiction under umbrella clause provisions embedded in the Switzerland‑Pakistan BIT. The tribunal rejected Pakistan’s narrow interpretation and held that the investor had incurred legitimate “investment” under the treaty, though it declined to treat purely contract claims as treaty violations absent clear intent. This decision shaped subsequent ISDS jurisprudence. According to UNCTAD, Pakistan was party to 12 ISDS cases between 2001 and 2022, with mixed outcomes: some settled, some in favour of Pakistan, others in favour of investors, and still others undecided or discontinued. The International News. unctad.org.

Source: Dawn

Future ISDS Risks and Policy Responses

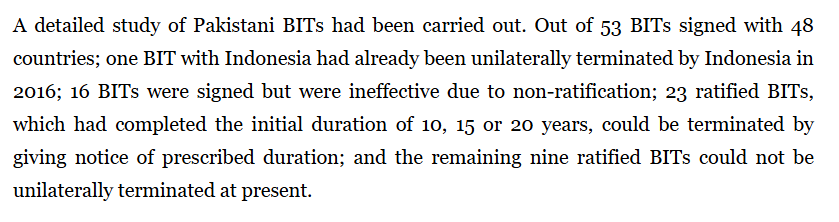

Termination of BITs and Treaty Reform

In response to growing arbitration exposure, Pakistan announced the termination of 23 out of 53 ratified BITs as of August 2021, particularly those containing ISDS provisions that limit regulatory autonomy. Pakistan also developed a new BIT template (per the 2013 Investment Policy) aiming to preserve policy space for public interest regulation, balancing investment protection with sovereign control.

Moreover, Pakistan is wary of multilateral treaties like the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). Critics argue that ECT membership could expose Pakistan to further high‑value claims by energy corporations challenging clean energy transitions or public interest policies. .

Transparency, Sovereignty, and Governance Concerns

Pakistan’s recent experience highlights systemic challenges:

- Transparency deficits: ISDS tribunals typically operate in closed sessions, limiting public insight into proceedings and outcomes, and fueling civil society concern over accountability.

- Regulatory chill: Facing potential multi‑billion dollar claims, governments may hesitate to enact environmental, labour, or taxation reforms, even when needed for public policy.

- Fiscal burden: Large arbitration awards, such as nearly US $6 billion in Reko Diq represent a significant share of Pakistan’s foreign exchange and debt liabilities, forcing the government to negotiate saddled settlements, deplete reserves, or restrict fiscal space.

- Impact on Economic Policy and Investor Confidence

Policy Shifts

Following these disputes, Pakistan has sought to recalibrate its investment framework:

- BIT retraction or renegotiation to reduce exposure to ISDS.

- New model BITs embedding clearer definitions of “investment”, “expropriation”, and FET, and narrowing umbrella clause scope.

- Promotion of mediation and dispute‑settlement alternatives to arbitration, such as state‑to‑state negotiation channels or in‑country dispute boards Investor Sentiment

Despite Pakistan’s resource potential, repeated arbitration defeats have made many international investors wary. Some caution that legal risks in Pakistan, compounded by policy reversals, exchange rate instability, and taxation unpredictability add macro‑political risk premiums to investment decisions (especially in infrastructure, mining, and utilities sectors).

However, for investors domiciled in states with reformed, balanced treaties, these issues may appear manageable. Recent settlements (e.g., Barrick reengaging with Reko Diq) suggest that investor confidence may return, so long as legal ambiguity is minimized and state policies remain consistent.

A Path Forward: Strengthening Pakistan’s Investment Dispute Framework

To mitigate future ISDS challenges and rebuild investor confidence, Pakistan must prioritize greater legal clarity and transparency. Embracing multilateral reforms; such as those under UNCITRAL, and promoting public hearings, consistent jurisprudence, and outcome disclosure can enhance the country’s credibility on the global stage.

At the same time, adopting a selective and strategic approach to treaty design will be critical. Rather than blanket commitments, Pakistan can negotiate future investment treaties on a case-by-case basis to protect investor rights without compromising regulatory autonomy.

Another important step is the incorporation of in-country alternatives to international arbitration. Requiring investors to first exhaust domestic legal remedies or participate in structured mediation before escalating disputes to international tribunals could reduce exposure to costly awards.

Additionally, to ease investor concerns over political and regulatory risks, Pakistan can utilize political risk insurance and risk-sharing instruments offered by global institutions such as the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) or the African Development Bank (AfDB).

These tools can act as safeguards that encourage investment while balancing the state’s right to govern in the public interest.

Conclusion

In short, the rise of ISDS cases against Pakistan culminating in high-profile disputes such as Reko Diq, Karkey, Broadsheet, and SGS, has transformed Pakistan’s approach to international investment law. With arbitration awards totaling billions of dollars, Pakistan has reexamined its BIT infrastructure, paused new treaties, and sought greater balance between investor protection and sovereign policymaking. While damages awards have dampened investor confidence, the prospect of renewed, clearly structured projects suggests cautious optimism remains. If Pakistan continues legal reforms, improves treaty coherence, and strengthens investment dispute resolution mechanisms, it may be able to restore investor confidence while safeguarding its policy space for public welfare.